THIS Is Why I Love Indonesia

I whine about Bali a lot, both because Bali and because British. But I love Indonesia. And this trip I’m on has reminded me why.

Because Indonesia is the only place in the whole wide world where you can set out looking for an island populated entirely by midgets and land up diving with whale sharks. (Probably also the only place where the equivalent of the head of a county council will invite you to his house to meet the spirits of ancestral kings, too.)

I am currently “on assignment” as ponces have it, or “working” as I call it, on the arduous task of researching islands off Sulawesi for a mag. (I’m also setting up a tediously factual website devoted to Indonesian islands, one of many dog-ate-my-homework reasons you haven’t heard from me for a while.) I also have to research some food stuff, which is obviously terribly hard work, and some culture, and I’m collecting a few more stories as I go.

Anywise, this weekend I, quite literally, set out in search of an island full of little people and ended up diving with the biggest fish on earth. Here, have a splendid deserted beach pic. I’ve got loads more where that came from.

In the course of researching islands – AKA talking to people and then more people until you find someone who knows or conclude that the only thing to do is get out there and have a look — I came across two possible amazing stories. One is true, and one, the island of the midgets, is less so.

But let’s start with Pak Ilham. Ilham’s father, major-general Andi Mattalatta, was known as the Rooster of the East during his heyday. This was a tribute to Sultan Hasanuddin, the 17th-century leader who managed to unify Sulawesi’s population, most of whom were more interested in piracy (coast), blood sacrifices (highlands), fishing (islands) and internecine strife (all of the above) than in the larger colonial picture, and lead a heroic if doomed resistance to the Dutch forces.

When dad retired from the army, still only in his 30s, he decided that what Indonesia really needed was water-skiing. And I defy you to imagine any more splendid sight in a nation which loves a good parade, is absolutely addicted to uniforms, and is a sucker for a schmaltzy tune, whether on the guitar or, even better, karaoke, than this absolutely splendid 1950s Indonesian water-skiing video.

Here, have a gander. It’s great!

And so Ilham, following in his father’s footsteps, decided to introduce diving to Makassar. He is, I will realise, an orang besar (big man) in Sulawesi.

Unencumbered by fripperies such as a website, a Facebook page or even, for that matter, a sign, Ilham runs the Makassar Diving Centre, cunningly concealed behind the parking lot of Kampoeng POPSA, the vaguely Singapore-style hawker court he’s set up where dad used to do his waterskiing.

An Indonesia novice would assume that any business without a website or street signage would be barely functioning and, when it comes to diving, more likely to kill you than not. Far from it!

Pak Ilham is a NAUI-certified deep dive instructor, has been diving for 40-odd years, operates a resort on the island of Kapoposang, and has an absolutely bona fide dive boat with two well-maintained 200HP engines, plus gear, plus staff, plus a professional compressor set-up. Further, he has sunk sundry items, including a broken down minibus, a jetski and some substantial classical statues off the island of Kodingareng Keke, to create an impromptu coral garden.

I explain I’m doing a diving and islands story for an inflight mag. Pak Ilham says the boat’s going to Barranglompo and Samalona tomorrow, and why don’t I join? In fact, I could dive with his family this afternoon if I fancied it? Sadly, I’m too busy trying to work out which islands are which to go diving that day.

I ask, tentatively, about the midgets. “Hmmm….” he says doubtfully. “I think there USED to be many midgets on Langkai, but with better nutrition and less – what’s the word? — incest, there aren’t so many.”

Nonetheless – and I recognise that curiosity about people of small stature is neither the most noble nor most cerebral of instincts – I am beginning to fixate on this island. Not least because I know that I will kick myself later if I am 20 miles from an island possibly populated by midgets and don’t get there. Here, have another beach picture.

You meet a nice class of people diving, I always find – especially in the more out-of-the-way spots. Our group comprises Yuda, the captain and dive guide, plus the chap who looks after the boat, plus Bert, a marine biologist looking to revisit an island he worked on 30 years before, Angel, a Chinese-Indonesian dentist whose parents used to let their house to scientists including Bert, and Anwi, who I don’t talk to that much because she’s rather vomitous and I’m being lazy about speaking Indonesian, but is clearly an extremely good photographer.

Our first stop is Barranglompo, the type of densely-packed, villagey Indonesian island of which I’m very fond – rather like Pulau Derawan, in fact. In one of those glaring contradictions that would drive all but the hardest-core fan of Indonesia screaming up the wall, it’s simultaneously a scientific research base and a centre for harvesting and culturing products for aquaria. Further, most fishing is done using dynamite, an activity on which the only possible positive spin is that it’s safer for the end consumer than cyanide. (I am far from hippie-dippie about toxins in food, but I won’t touch small Indonesian fish unless they’re in a restaurant I know and trust.)

The diving is about as rubbish as you’d expect, with equipment problems adding an extra layer of magic to the sheer joy of diving on devastated sand in murk. However, it’s interesting to watch Bert at work, bagging his specimens neatly, and fab to watch Angel, who’s won prizes for underwater photography, doing her stuff too.

On land, it’s fascinating. They’re farming seahorses – poor little seahorses! They’re cultivating gloriously coloured giant clams. And they’re snatching soft coral after soft coral for some fancy aquarium somewhere, and storing them in concrete channels full of seawater.

We stop at the home of an old friend of Bert’s. He and his daughter – who’s just learned to dive with the current batch of scientists – welcome us in. He lost his son recently, in Kalimantan, diving, Angel tells me.

Out comes the mobile, and on goes the video, with footage of her big brother’s body being dragged from the water. Questions that my English mind consider intrusive, such as how bloated he was, go back and forth, and the ritual wailing stops as we pause the video to inspect the head wound they think killed him.

“He was spearfishing a big fish,” Angel explains.

“Oh,” I say. “So the fish took him and dragged him down?”

“Dragged him into something,” she says.

I find it difficult to look at his corpse. In my culture, death is private, secretive, almost every element of it, from care of the dying to preparing the body, from flower arrangements to diagnosis, is professionalised and hidden. I’ve been to cremations in Bali and watched bodies go up in flames, which I suspect is an easier way to process death than watching a sealed coffin slide behind a curtain, but my death taboo still stands.

His father brings out photos of his handsome son posing with enormous fish – 80- or 100-kilo monsters that could easily drag a spearfisherman to unsurvivable depths. Here I can say something. “He was a good-looking man,” I say. And he was. A stunner.

Death comes frequently in Barranglompo, I learn: as on the Philippine islands not so far from here, commercial diving is done hookah-style, using a pipe attached to modified truck brakes, with close-to-zero measures to prevent death from the bends or, for that matter, good old diesel fumes.

Samalona is our next stop, an island that’s on the backpacker radar already (the Millers spent some time here in 2013). Which is to say it’s bloody impossible to walk past Fort Rotterdam, the old Dutch trading fort in downtown Makassar, without both becak drivers and boatmen touting trips out to it.

The diving is better at Samalona. We’re all fundamentally tagging along as Bert, who’s been diving off interesting islands for a living for over thirty years – and can we all say three cheers for the absolutely bloody fantastic career choice of being a marine biologist?! – whizzes along the current looking for stuff, but there’s clearly interesting weird stuff to be seen when you’re not chasing after a coral-crazed scientist.

I request a stop on shore: it’s the dinkiest island and I want to take a look. You can walk across Samalona in approximately 90 seconds, and there really isn’t much to it, but I figure it might be a splendid place to pass a night or two – there aren’t just rooms but an entire house for rent — and I note that the warung sells beer. Yay!

I ask again about the little people, whose putative island is now whizzing around my head in big tabloid capitals – INDONESIA’S ISLAND OF THE INCEST DWARVES. Part of me, however, is beginning to wonder whether both this and the possibly-legendary leopard people up north may just be a genetically challenged group of individuals, rather than an amazing off-the-path story.

The name Langkai keeps coming up. Therefore I need to get to Langkai. Here, have another island picture. You’re welcome.

There is, of course, the actual commissioned element to arrange. I want to get to Kapoposang, where Ilham has his beach bungalows, again unencumbered by any form of digital marketing, which makes sense to a degree given there’s no phone signal on the island.

Obviously, the mag doesn’t pay expenses – who does, nowadays? But, when it gets around to it – that’s 60 days after publication or many months after work has been done — it does pay enough to cover a reasonable amount of research and travel, even if most of the profit comes in on other commissions around this base story.

We work out a deal where I’ll cover staff wages on the island, tip the crew, buy food for myself and purchase the not-inconsiderable quantity of petrol required to get to all these islands; boat, dives and gear come free.

So, I’ll go with Yuda and his helper – whose name I cannot remember, and by the time you’ve got horribly drunk with someone on an island it’s far too late to ask – to Kapoposang. We’ll stop at another island someone has told me about, which is apparently the prettiest of the group. We’ll dive Kapoposang and overnight in the resort.

Then in the morning we’ll pop in to check on the incest dwarves, stop at Kodaringeng Keke to check out the sunken bus, and head back to Makassar. This seems like a decent plan for the weekend.

It’s also, I realise, the kind of proper worky travel writing – as opposed to doing fun stuff and writing about it – that would drive my spawn absolutely bloody bonkers, or, rather, leave him sellotaped to his computer. He’s staying with friends on Bali, then off to school camp, while I explore.

I spend an absolutely splendid afternoon buying maps, sampling yet more of Makassar’s fantastic food, and meeting a chap who explains in patiently simple Indonesian how the hundreds of islands off these shores join up. I have neglected to bring my dictionary, but all this enforced Indonesian language conversation is helping my language along no end.

And setting out on the boat, I realise how very much I like my life. It’s a paradoxically pretty journey. Makassar is a major port so bigass tankers and container ships come right into the harbour, close to shore and right in the heart of town, although there’s a second at Paoetere for sailing ships, big fishing boats and public boats to sundry archipelagos.

Multi-storey blocks, container cranes and tankers fade behind us. An ocean studded with white-sand islands stretches ahead of us, clumps of forest just popping out of the sea. There HAS, I feel, to be something absolutely great out here.

And Kapoposang, two hours from Makassar by speedboat, is wonderful. We dive with sharks – two big ones that come a little close for my comfort, though Yuda’s relaxed and reeftips have hardly ever taken so much as a nip out of a human – not to mention turtles, tuna, trevally and barracuda, moray eels and pretty things.

I try and fail and try and fail to get the money shot of turtles taking off from the wall with its pretty sea fans. But I can’t get both turtle and wall into a composed shot.

And then Yuda and his mate, good Indonesian Muslims that they are, break out a crate of beer for sunset and I improve my Indonesian language skills yet more.

A fisherman swings by, through the shady forest that lines the white sand beach. There are whale sharks off the island, he says: eleven of them, following a school of tiny fish and krill that comes through regularly around this time of year.

He gives Yuda, who knows the islands backwards, directions to the spot.

“Do you want to see the whale sharks?” Yuda asks.

DAMN RIGHT I want to see the whale sharks. I cannot imagine a single diver who would not want to see the whale sharks. The gentle giants of the shark world, they cruise the globe following patterns that no one fully understands.

People fly thousands of miles just for the chance to swim, snorkel or dive with whale sharks. And I don’t have to choose between whale sharks and midgets – the whale sharks are actually en route! It’s a 100% Indonesian piece of serendipity. I’m super-chuffed I fronted up for the extra 50 litres of petrol.

More beer is drunk and I improve my command of Indonesian obscenities no end.

All of us are a little under the weather at 6am the next day – in fact, having missed the sunset due to washing, I almost miss the sunrise too. Following three hours of reasonably deep diving with five bottles of Bintang is not exactly what the dive books recommend, but I eat, hydrate and caffeinate, and we leave at 7 as planned.

The whale sharks’ presence is hard to miss. Every single fishing boat from every single tiny island is out here, stretched like strings of bunting along the pancake-flat sea. There’s joy in the air. The catch is boundless! Polystyrene crate after crate of tiny fish are loaded. Men grin below the makeshift turbans that shield them from the sun as they haul in nets and pick out their silver catch. Some boats are tag-teaming – running loads back to shore to store on ice so that others can continue to harvest this marine bounty.

Yuda pulls out a carrier bag and swaps some of the dreaded Aqua glasses to fill the bag with fish.

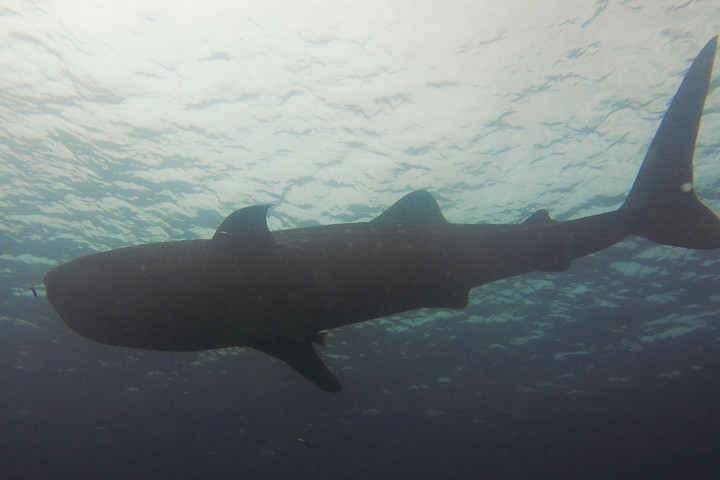

And, OMFG, a whale shark! The first one, maybe three meters long, leopard-spotted and graceful, glides beside our boat, a fleeting vision: we squeal and snatch at pictures.

But where are the rest? We to and fro among the fishing fleet, taking directions every which way. They’re always somewhere else, but there’s a big one, seven metres long, somewhere out there.

“Snorkel?” Yuda asks.

I’ve been stripped down to my culturally-more-appropriate vest-that-should-really-be-a-T-shirt and shorts-that-should-be-a-bit-longer-this-far-out snorkelling outfit for a while. Flippers on, and we’re in the current, me following Yuda. He shouts through his snorkel: another! There are mantas, too!

“Want to dive?” Yuda asks.

“Yes,” I say.

I must admit that I’ve retained some baseline diving trauma – rescue course notwithstanding – from Zac’s death drop in the Blue Hole. I love diving. But bottomless walls and strong currents make me nervous – despite the fact I love what you see down there.

Diving a brand new site, surrounded by fishing nets and fishing boats, in the open ocean with unknown currents, is a big step for me, and involves a lot of trust. I trust Yuda, not least because he went diving in Bali and decided against diving Tepekong, an amazing but famously difficult and dangerous dive site, because “he’d rather live”. (I might consider this when I bank my thousandth dive.)

“No more than fifteen metres, and not on the wall,” I say in rubbish Indonesian. The site is a sandy bottom that looks to me like the top of a sea mount, which means there could be all sorts of nasty currents – down, up, out to sea, down and out to sea… – around the edges. On this, it appears, Yuda and I are aligned. “Have you got reefhooks?”

Yuda has two serious-ass reefhooks: not tent pegs on a rope, but bona fide claw anchors. I take one, he takes the other, which means if something hideous happens with the current, or if we find a spot we want to stop at and the current’s too fast to stop, we can anchor ourselves to the reef.

I do my usual checks – I’m mildly OCD about pre-dive checks by many people’s standards, and make myself do them even when we might miss something like a whale shark – and roll backward off the boat, Yuda gives the signal, and down we go.

Seamounts are interesting places – I’ve dived with thresher sharks at one on Malapascua, and with hammerhead sharks off another on Malapascua. They seem to function a bit like service stations on the ocean road: sometimes they’ll have entire coral gardens and cleaning stations, with fish waiting for their larger clients to come along, sometimes they’re just flat and dull.

This one’s pretty bland, apart from the sharks, and decorated with long fishing nets rapidly filling with catch, which also can’t do the coral any favours. We’ve just got down when Yuda squawks through his regulator. There’s a whale shark cruising right above me, a juvenile, just three metres long.

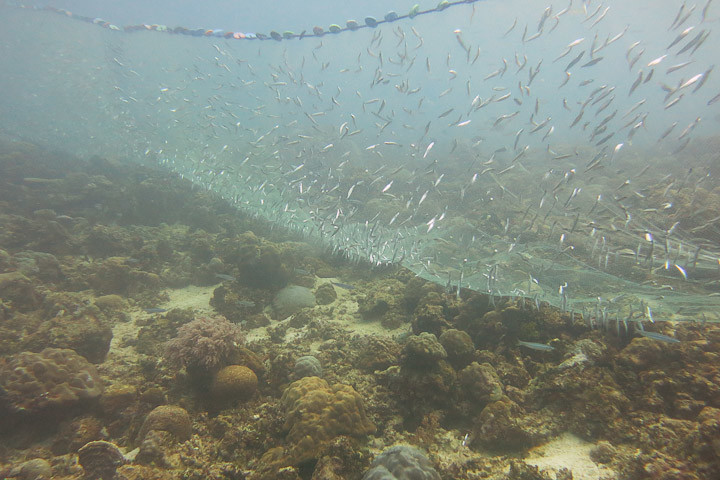

I bang out a couple of photos, realise I won’t get a decent shot without a wide-angle lens and a strobe and exposure control, and resolve to just watch the sharks instead. This irritates Yuda, who can’t see why on earth someone would be in the water with the world’s largest fish and a camera and NOT take pictures, so he takes my camera, which I’m cool with. The fishing net shot above is his, and I think it’s really rather good.

Then we’re in the cloud of krill. It’s like diving in fog – I even think my mask has fogged, but when I look up to the surface or close up at my computer, there’s no fog there. I follow Yuda. For ten more minutes, we fin along the seamount, down and up over the unbeauteous corals and sea grass.

No more whale sharks. Yuda calls the dive. We only have a tank each, and another dive to do. Slowly, we ascend to safety stop depth.

And it’s my turn to squawk through the regulator. “Wark!” I yell, articulately, as we hang in the water.

There’s such a majesty to sharks, all kinds of shark. They just materialise out of the blue water, almost ghostlike, like Polaroids onto paper. One minute there’s nothing. The next, there’s a shark. And then they fade away again. Even scientists don’t know where sharks go, or even how they navigate – the best bet is a form of geomagnetic sensing in which sea mounts may play a part.

This one is perfect, the textbook picture if one had the timing and equipment.

It’s right behind Yuda, heading towards us, wide mouth gaping, sieving krill. Cleaner fish hang from its belly like streamers, feasting on parasites (fun fact! Sharks get STDs too).

It’s perfect, just textbook perfect, and as we emerge, we’re buzzing. White sand island, whalesharks, what could be better? Well, midgets, obviously.

And, I realise, I think this dive into the unknown has finally cleared my diving trauma.

While we’ve been diving, Yuda’s mate has been chatting midgets with the fishermen. They’re not on Langkai, the island we thought they were on, but Lanjukang, the one along from it, a pretty little place with a gorgeous golden sandbar.

There are only 15 families on Lanjukang – Langkai is a metropolis with 300 households! – but they and the fishermen who frequent the seamounts around here support a little warung. The lady has – yay! – coffee and – major yay! – believes Yuda when he explains in considerable detail to a group of curious islanders how the crazy bule doesn’t like sugar or even sweet milk, or anything sweet, not even sedikit, ta muchly.

We sit in the makeshift bale and chat as I drink my coffee. Apparently, two Spanish and American tourists came through only a month ago, making Lanjukang quite the destination and causing quite the stir. It boasts a rather optimistic sign with a map of the island likely created long after dynamite fishing nuked the reef.

There’s a man who knows the midgets, and can bring us to them, but we’ll have to pay if we want a photo. Yuda thinks I want a photo. For some reason, he also thinks I’m writing a book, or, possibly, he’s just decided that people here will understand the idea of writing a book better than they will the idea of an inflight magazine based in a country that’s neither Indonesia nor England. I resolve to bring mag copies with me next time I do this sort of thing.

I don’t really want a picture of me with some people of short stature (hell, I’ve been to Hobbit House in Manila). I wanted to find the island of the midgets. However, this appears to be the island of the midgets, and, further, the midgets’ significantly-larger but still-not-actually-terribly-tall brother is coming to meet us, so I’ll pay for the photo and bung a few tourist rupiah into the economy.

Amazingly, the midgets’ brother speaks some English! He has an Indonesian book of conversational English, and assuming that the English conversation you want to make is an outtake from Brief Encounter – “Good afternoon! This is my friend, Smith!” – I’m sure it could work rather well.

And, lo!, behind him, his brother appears. He’s about up to my waist but in proportion, with bandy legs and a facial structure that suggests Pak Ilham may have been on the nail about inbreeding. In the days before the outboard motor, when the siblings were born, the genetic pool must have been tiny. We make introductions, and off we trot to Casa Midget – or, rather Casa Brother Midget.

I don’t want to take these people’s photo. Or, rather, if I had the time to do a proper study and place them in their home and their environment and talk to them properly which would require a translator since my Indonesian isn’t good enough for nuance, I would like to. As it is, I’m objectifying these poor people horribly.

I realise, in fact, that I hadn’t got any further in thinking about this story than: “Find out if the island of the midgets exists.”

There are two midget brothers and a sister. The men work in fishing. The sister keeps home. We are all equally unenthusiastic about the picture, but Yuda takes one, me a giant in a wetsuit with mask hair, the three of them together. And, at least when I look at the picture, it really is me who looks out of place and wrong-sized, not them.

Then we talk money. Yuda thinks 100,000 is fair. I hand over 100,000. The brother wants another 50,000, at which I initially baulk – that’s crazy money out in the badlands of the Spermonde islands – but he explains it’s 50,000 for each of the siblings, which, both Yuda and I agree, is fair. Dimly suspecting the life of people of short stature on a remote Indonesian island is far from the bliss of that gold sand beach, I don’t nego.

Job done, we head back to the boat. “They live in the forest, the midgets,” Yuda remarks darkly as we leave. I am still processing this.

So terribly wrong and yet, so right…

Indeed. I felt quite ashamed of using these poor people as a human zoo, and then I thought, ah, fuck it, it’s Indonesia.

Well you afforded them an income based on their unique virtues and qualities after which they were less poor than before. What was Maria Callas but a shrieking freak? Part of life’s great big cultural menagerie, it’s all just a matter of scale, context and production values.

Hope you are still having fun there. Been there 5 times now and love the place. My greatest memory was watching them catch fruit bars with kites in Java, seen that?

No, not yet! I’ll add it to my list along with the whale hunt and pygmy elephants.

I’m proud to be Indonesian People..

Thank you for tell your story about Indonesia..

Gotta love Indonesia! An adventurers paradise in my book. I feel sorry for all folks that visit Bali time and again (my neighbours been 40+ times) but never explore any further afield. Oh well their loss…I’m pretty keen to do some island hopping to the east of Flores, including Palau Lembata without actually witnessing the whale hunt. Still A little disturbed from seeing chunks of dolphin meat for sale at roadside fish stalls.

Are you sure is this the only land up diving with whale sharks. Anyways very inspirational article. I love the writing along with the excellent photos that made this article alive.

I’m sure it’s the only place where you can start looking for an island of the midgets and end up diving with whale sharks, yes.

I never visited Indonesia, and your post only caused MORE DESIRE to go to this exotic and marvellous country 🙂 thank you! Post more about new countries, and, please, post something about my country, Brazil. I love learning about countries 🙂 these things make me happy.

That’s good to know, Rosita!

Thanks to visit and tell others about Indonesia. Have a nice trip.

These are just some of the many reasons why Indonesia is loved by many people. The country has a lot to offer to people who loves traveling and adventures.

Indonesia is so endlessly interesting … loved the deserted beach pic at the start!

Thanks for sharing about one of the wonderful exprerience of Indonesia’s tourist destinations and Indonesia has more then 17,000 islands where you can explore and they have their own unique beauty that probably you have never seen before. They have lots of different culture for each place you visit and they even have at least more than 300 languages but most of them understand the national language which is called Bahasa Indonesia.

good writing. thank you

” I am beginning to fixate on this island. Not least because I know that I will kick myself later if I am 20 miles from an island possibly populated by midgets and don’t get there.”

HAHAHAHA! Brilliant!

Merci!