Conquering (?) Vertigo in Tiger Leaping Gorge

Z jumps from stone to stone across the waterfall which tumbles in a rocky stream across the cliff-edge path and a mile or so down grassy rock, autumn wildflowers and orange-tinged spruce into Tiger Leaping Gorge.

A candidate for the deepest gorge in the world, Tiger Leaping Gorge is the place in Yunnan, China, where the Yangzi river narrows so much that the gorge is wide enough for a tiger to jump across — and, so the story goes, one did.

And now, high above it, my son is jumping. Across a waterfall.

I bite back the urge to yell, “Be careful!” Something that, like most parents who are scared of heights – and probably plenty who aren’t — I yell a lot.

Instead, I plod leadenly through the running water, chanting, as I have been since the unfenced path narrowed to shoulder breadth and the walls of the gorge went from steep to pretty much sheer: “There’s a solid rock wall on my left. There’s a solid rock wall on my left. There’s a solid rock wall on my left. I’m doing fine. I’m doing fine…”

“Aren’t your feet cold?” asks Wangmo, our guide.

I realise that in my urge to walk across without holding her hand I am a) walking in the mountain stream and b) bent almost double to hold on to the stepping stones.

Vertigo 1. Dignity 0.

Hey-ho. Though, as vertigo therapy goes, hiking Tiger Leaping Gorge has a lot to recommend it.

We’re here on a jolly with China Odyssey Tours. China Odyssey does small group tours, which means they design a tour for you, the folk you’re with, and, umm, no-one else.

Which, when your “group” comprises one ten-year-old boy and one adult of dubious fitness, once sufficiently scared of heights to be freaked out by a Bangkok roof bar, now marginally better after a month living on the 32nd floor, helps a LOT.

It means we can avoid the perilous Ladder to Heaven, an unshielded, wobbly ladder, ascended without carabiners or safety line, that runs several hundred metres in three stages down and up from the river near its narrowest point.

We can also walk at a pace that’s basically ours rather than that of a group of 20-somethings.

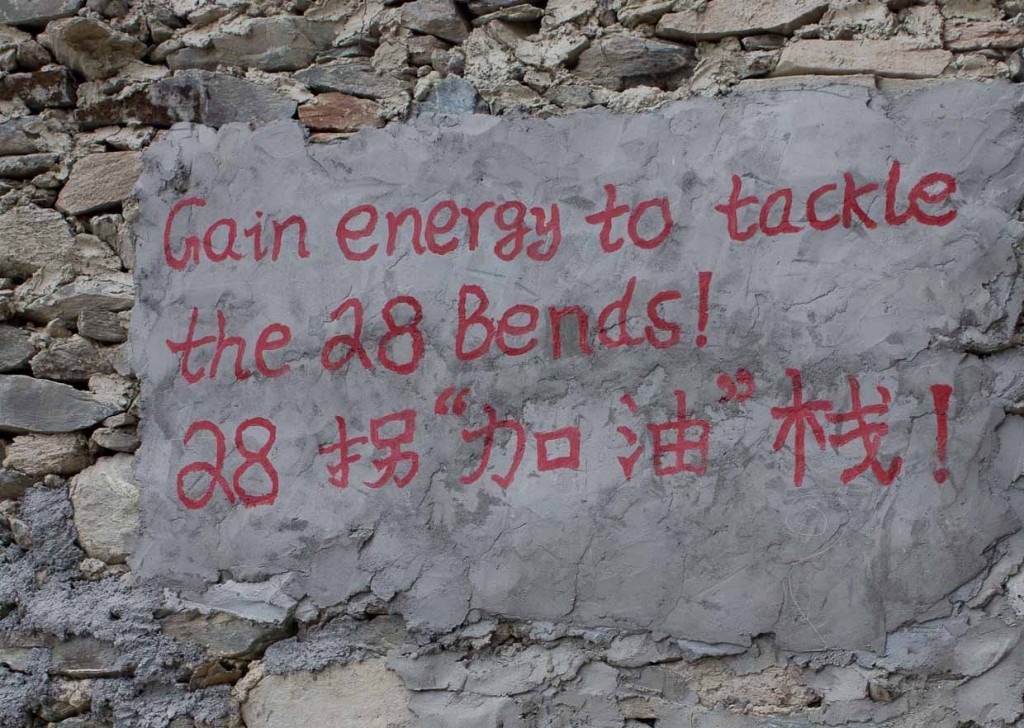

Why do a walk like this when you’re out of shape? Well, given what we’ve heard of a challenging stretch called 28 Bends, I figure it will get me back in shape.

Why do a walk like this when you’re scared of heights?

Partly, I’m hoping Tiger Leaping Gorge will do what zipwiring has not, and help cure my vertigo.

Mainly, though, because it’s beautiful, quite dazzlingly so.

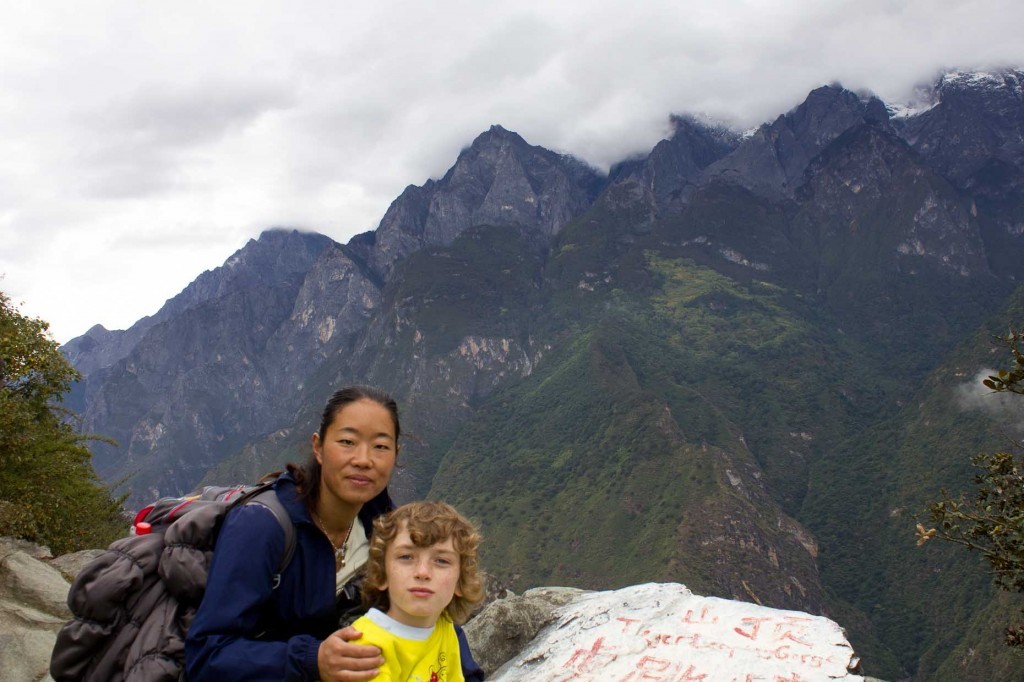

Winding round a curve in the gorge, clouds wreath the lower, snowy slopes of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, a 6000m virgin peak, sacred to the Naxi people, the tribal minority who have occupied this hinterland since time immemorial.

“I wish I could fly,” says Z. “I wish I had wings so I could fly over the river to all that lovely snow.”

Below us the Yangzi, called, on this stretch, “Long River”, is narrowing and beginning to roar as the gorge tightens from the gentle slopes when we set out.

“I don’t like heights either,” says Wangmo, sympathetically. She’s Tibetan, from Shangri-La, a tourist boom town a couple of hours north of here. “When it’s steep like this, my heart goes boom-boom-boom-boom-boom.”

You can only tell if you’re afraid of heights yourself. On steep, narrow, unshielded corners, Z walks round like a normal adult. Wangmo’s hand, like mine, goes out to touch the rock beside us. Not to grip it. Just to reassure her that it’s there.

I cannot, however, see her lips move in the vertigo sufferer’s mantra at any point. And she certainly doesn’t slow to the crawl that I do.

But then I’m too busy not looking down myself.

“I walk like a horse,” says Wangmo, miming blinkers over her eyes. It’s a good quality in a mountain guide, I figure, a mild fear of heights.

It means that she can actually empathise with people like me who have to chant a bit when you can’t tell the path from the waterfall but your imagination can conjure up a million ways to fall…

Setting out from Qiaotou, the thrown-up little town at the head of Tiger Leaping Gorge, Z is not in the best frame of mind. Now, he’s a tough little walker when he puts his mind to it.

In Borneo, aged nine, he reached the summit of Mount Kinabalu, a task plenty of fit, 20-somethings fail at.

In the jungles of Halmahera, Indonesia, he walked tribal paths for almost a week to meet nomadic hunter-gatherers. He’s hiked the Ho Chi Minh trail in Cambodia, and the spirit-filled forests of Northern Laos.

In fact, he can wield a machete like, umm, well, let’s just say rather better than me.

And on EVERY SINGLE ONE of these treks our first three or four kilometers has proceeded at a quite spectacularly sullen dawdle that puts the aggression into passive-aggressive.

We have 18 kilometres to cover before dark, including the dreaded 28 Bends.

We’re ascending, in fact, only from 1800 metres to 2600 metres. But to arrive at 2600 metres we have first to ascend to 3200 metres, almost all that ascent compressed into a couple of kilometres around 28 Bends.

Before that? Well, it takes us an hour to cover the first 2 kilometres of easy walking, some of it, in fact, on tarmac.

When Z is not sulking he’s taking photographs – he loves the wildflowers here even more than I do.

As late as the 1950s vast mule caravans swept through this region, bringing Southern Yunnan’s pu’er tea, compacted for the journey into bricks so tough that the tourist places today sell teapots made from them, into Tibet, whence they returned with horses.

And, despite the influx of wealth which means that Naxi homes which were crumbling farmhouses a decade or two ago now boast swep’-up tiled gates and real cars in their driveways, there are still plenty of working animals up here.

We pass an eight-strong train carrying maize from the vertiginous fields, led by a teenage girl in skinny jeans, texting on her mobile.

Still, the older Naxi muleteers take every opportunity to augment their income, when returning unladen from a trip to Qiaotou market, by carrying Western tourists up 28 Bends, and further.

After one look at Z’s physique and pace, this chap follows us like a deathwatch beetle – shades of our friendly vulture in the Ijen.

I address my spawn in a manner that’s half motivational speaker, half wheedling parent. “Remember Mount Kinabalu? That was tough. This will be EASY compared to that. But you WERE really pleased you did it at the end and at how beautiful the sunrise was.”

“Humph,” he says, huffily. “I went through that entire hike with my eyes half-closed saying ‘I can do this’, ‘I can do this’.”

“Yep,” I said. “That’s one way to do it. And you did it! And you do like trekking once you get into it.”

“No I don’t,” he says.

“Yes, you do,” I insist. “You always like the beautiful things we see. And the sense of achievement. You have liked every trek we have been on.”

“That’s because I had a reward for each one,” he says.

“No it’s not,” I say. “Every single time we have done a trek you have whinged for the first hour or so and then got into it and started enjoying it.”

Whatevs. We agree a bribe – I’m sorry, I mean, of course “reward” –- for completion of the trek in good time, with minimal complaining and without assistance. He opts for The Sims.

Wangmo has a six-year-old son, which makes her no slouch at motivating young males who find it difficult to combine walking and talking, and like to talk a LOT.

As we head up the first steep section, Wangmo goes to the front to set the pace, while I follow behind to chivvy, leaving poor Z sandwiched between two mothers.

“Come on!” yells Wangmo, steaming up the hill. “Don’t you want that Cola with your lunch?”

“Think of your Sims family,” I pant from behind. “They need you!”

“Think of the Sims,” echoes Wangmo.

We’re like some harpie chorus, bracketing him all the way to the Naxi Family guesthouse where we break for lunch. It’s full of drying corncobs and peppers, and the fresh flowers which bloom here much of the year.

We take our seats. “Oh,” I say. “What’s that fur on the chair?”

“It looks like dog,” says Z.

“Yes,” says Wangmo, checking the dangling paws. “I think it’s something like dog.”

“Oh,” I say, with British naivety. “A fox, maybe?”

“No,” says Wangmo. “Just dog, I think.”

While I can’t, from an ethical perspective, see any difference between sitting on a dog fur and sitting on the skin of any other unendangered domestic animal — cow, horse or reindeer –-, cultural conditioning kicks in. Neither of us sits on that chair.

Z orders extra Sichuan pepper with his lunch to balance out the chilli, consumes gallons of green tea and takes a ton of flower pictures.

And, once we start walking again, he’s in a groove. Me? My calves are burning. And I’m really wishing I hadn’t brought my MacBook (long story).

My pack’s probably only 5 or 6kg. But that’s about 3kg more than it needs to be, and I’m feeling it.

Our first steep stretch, and Z comes into his own. He keeps pace with Wangmo effortlessly while I lumber, panting, behind them.

The muleteer, who has waited, discreetly, while we lunch, realizes the game is up.

“Can you move?” asks Wangmo. “He wants to get past.”

We squeeze out of his way. “Oh good,” Z says. “The mule guy’s given up. I’m totally going to do this.”

“I know you are,” I say, “You’re a good strong walker.”

“I think I’ll have three kids in my Sims family,” he says.

We hit a view. “Wow!” he says. “This is beautiful.”

“See!” I say. “I told you you’d like it once you were in it.

“Oh, alright,” he says. “I do kind of like trekking.”

“OK,” I say. “I want that in writing for next time.” (He has, indeed, put it into writing here.)

At a little shack before the dreaded 28 Bends we discover the joys of Chinese pear eaten crisp, sweet and tangy, and Z contemplates, debates and then abandons his third ill-advised knife purchase of our trip.

The stretch is rocky, steep and winding – so winding that Z and I both count north of 30 bends, and Wangmo’s 28 is distinctly unconvincing.

Z? He’s pretty much gamboling. Wangmo? Well, she’s Tibetan and lives at a higher altitude than this, so hills hold no fears for her.

Me? I lumber and puff alarmingly, breathing harder as the air thins a little towards the top, calves howling a vigorous complaint. We break every ten or so bends.

But at the top – oh what a view, even in the mist. Prayer flags over a sheer, steep drop down to the Yangtze and a hint of the snowline of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

“And you know what, Mum?” Z exclaims, not breathless in the slightest. “That wasn’t HALF as hard as I’d expected.”

And then? Even better! It’s downhill…

All the way to Tea Horse Guesthouse, hot showers, Naxi cheese and flatbread, forest mushrooms and, as the chill draws in, electric blankets too.

The walking’s easier the second day and, let’s say, a good challenge for my vertigo. The slopes go from steep to sheer for a stretch, the path almost carved into the cliff, huge unfenced drops disappearing below us on corners.

The waterfall is the hardest bit, and I wonder how the French family we met back at Naxi Family, walking the gorge in 5 or 6k bites with a 4-year-old and a 6-year-old, will cope.

“They’ll use mules,” says Wangmo. “They’ll need to. You can’t take a six year old on this path.”

And we wind down through farmhouses to Tina’s, where we will spend our second night, not so far above the river now.

“Do you think we can walk to Walnut Village along the river tomorrow?” I ask Wangmo, flip-flopped and slurping coffee, oleaginous with yak milk, safely at Tina’s. It’s something we’ve been chatting about as we walk.

“The path down is kind of dangerous,” she says. “It can be very slippery and it’s narrow in places. It’s also very steep. I think Z’s too young. But you see and you decide.”

But the river’s so NEAR now! I want to go down to it. I want to see the place the Yangzi narrowed enough for a tiger to jump it before I see it sprawling, vast and estuarine, into the sea at Shanghai

We leave Z at the guesthouse with Doctor Who and pick our way down through steep fields to the head of the path, along with Li, another guide, whose clients are flat-out but who would like to scope the path as well.

By the time we get there, it’s pushing 4pm. A Chinese couple emerge from the trail. “One hour down, two hours up,” they say.

Not at the pace Li goes, it isn’t. He’s galloping. Scampering down the steps and pausing at corners to wait for us.

Five minutes in and I can tell there’s no way I’m taking Z up the return path. You can see it here, hacked into the cliff on the left.

There’s a chain, of sorts, in places, but it’s not really much by way of protection against certain death if you skid on one of the painfully steep corners.

Even on our path, some of the corners are so tight and rocky, some with streams running over them, that we ascend and descend, as Li puts it, “like animals! Like bears!”. But the chain provides a sense of security and I’m pleasantly surprised by how not-afraid I am.

And then we’re down. There’s the rock that the tiger jumped to – and suicides jump from nowadays, the bodies all washing up at a bend in the river downstream.

A view up a waterfall to a road bridge, lego-block-sized, high above us. And the Yangzi roaring like a hundred tigers — so narrow, for such a major river, and yet so fierce.

The next day, as we embark on a ridiculously easy amble to the village down the road, it’s with a sense of real achievement.

Tiger Leaping Gorge 1. Vertigo 0.

And my legs don’t even hurt!

What a beautiful place. Ok – need lots of energy but I think it is wonderful that your son is experiencing places like this at an early age.

Thanks, Natalie. It is stunning. Just wish we’d had more photogenic weather…

The Sims need more Moms like you too… love it!! 🙂

Thanks, Raymond.

I’m so glad you wrote about this … it is something I will never do and glad I get to live vicariously through you. Sounds amazing, and really difficult!

Thank you! It wasn’t actually that difficult — Kinabalu’s our benchmark for difficult (my knees were alternately shaking and locking by the end of that one) — but still quite, umm, energising…