My Father, The Headhunter

Kores holds his father’s weapons proudly in his hands. A short, broad machete, wrapped up in ikat cloth and string, and two crude wooden spears.

His sight’s fading now – one eye shut, almost gone the way of his teeth, and there’s a goitre on the back of his skull bigger than either of his round cheeks.

Kores can’t chew betel now. He pounds the nut, instead, in a little metal tube, to a consistency he can satisfactorily gum.

“Did your father take heads from women and children?” I ask. “Or just from men?”

“Children?” he echoes, and looks to his son-in-law for affirmation. “It’s better he tells you this, because his mind is still strong.”

Andreas, Kores’ son in law, resplendent in a red T-shirt advertising plastic bags and a sarong almost as scarlet as his betel-stained lips, picks up his story. His Indonesian’s better than his father-in-law’s.

He can write, too. In fact, he’s fresh from a local council meeting, notebook under one arm. His two small sons bury their heads in his sarong, looking up from time to time at these large, pale intruders.

“No,” he says. “We never took children’s heads. Not for eight generations. For eight generations…” he pauses to spit the scarlet betel juice… “We take only the heads of adult men.”

The smoke from the open fire blows straight into Z’s face. He coughs.

The family seem surprised. Smoke doesn’t bother the children here. They are kippered in it from birth.

We’re in Timor – Indonesian Timor – in a village called Nome, supposedly the last head-hunting village that’s left here.

It’s a peculiar place. Low, circular beehive huts, their smoke-blackened thatch descending almost to the ground, line a bright clay path, framed by sugar palms and, incongruously, eucalyptus.

The village sits around what must once have been a most spectacular fort.

A wall of jagged coral rock, cannibalised now for gardens and paths, stands only a metre high, though it once stood half as high again.

A couple of archetypal Wild West cactuses sit on top of it – the remains of a formidable line, a type of natural razor wire.

Cliffs drop away 60 or 70 metres on three sides, shaded by trees that shield defenders but offer the most spectacular view.

“This is where they plan the attack,” Aka, our guide, explains, as we stand by the shady platform where the headhunters held their councils. “If they are coming from the north, they measure with a stick towards the north, and if the fingers don’t reach to the central pole, the man will die.”

One of the young guys from the village demonstrates, whirling the stick around and stretching.

“That’s the only way?” I ask.

“No,” he says. “They can try a second time. And if that fails, they ask the eggs. If there is blood in the egg, the man will die.”

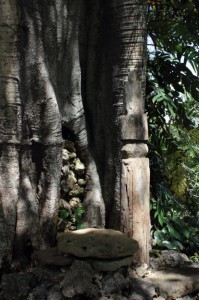

I nod. We pose for photos on a sort of totem throne under a strangling fig, a tree that’s sacred all over Asia – they call it the Buddha tree in many places – and here houses the souls of the tribal ancestors.

It is, as they say, a far cry from Kensington. Or Hackney, for that matter.

Outside their new hut, Kores’ wife smiles broadly and hands around a bowl of sweet potatoes, young, pale tubers fresh from the red earth. I pop one out of its skin and nibble. It’s delicious.

“What did they do with the heads?” Z asks.

“They give them to the king.”

I rephrase, and Aka translates into Dawan. “When they take the heads, where do the bodies go? Where do the heads go?”

“The king takes the heads, the Nope of this kingdom. The heroes wait with them for four days and nights inside the fort, and then they bring them to the king.”

“The bodies?”

“They leave the bodies there.”

“What happens to the heads?”

“The king! He keeps them.”

“What happened to the heads when they weren’t allowed to hunt them any more?” asks Z.

Silence. No one knows.

Head-hunting Nome style sounds, as they tell the story – and who would not tell their grandfather’s story well? – like a positively courtly ritual.

Before he was allowed to hunt for heads, a man must reach the age of forty. Only the strongest men could hunt — a practice which sounds, in evolutionary terms, like a way of disposing of the community’s alpha males.

The greatest warriors, men like the three famous brothers, Oni, Boi and Kao, would be dubbed by the king with the title “Meo” – for all the world like medieval knights on a quest.

“Were there other villages hunting heads here?”

“Only Nome.”

“So, no one else took heads? Only you?”

Only them. Only their warriors went out in search of other villages’ menfolk. Though the two other kings in the region had their headhunters, too – the Nome people say.

When the warriors came in, heads slung over their shoulders, blood coagulating from their severed necks, the whole village, men, women and children would celebrate, eating, drinking and dancing in the fort.

Many houses in the village are as they always were in the headhunting times. There’s much less modernization here than in the Borneo longhouses.

It’s a good defensive strategy, no question of it.

Watching Z, who is, at ten, on the taller side of the older adults in the village, entering the beehive huts, he’s bent more than double. An invading warrior would die a hideous, and undignified death.

As a way of life?

Well, the circular huts are perhaps a little over 3 metres in diameter. The door is under a metre high. The ceiling is a little over a metre above the dirt floor. From the branch rafters, corn hangs to smoke in the cooking fire that barbecues everything to sooty black.

There are no windows. No chimneys. When the door is shut, the smoke seeps out around the edges of the door and through any loose patches in the thatch.

When a baby is born, here, the placenta is buried in the floor of the hut. A flat stone goes over it.

The mother and baby have to spend the first forty days and forty nights inside the hut, kippering – and, as a smoker, I do not use that phrase so lightly.

“My god,” says Z. “Their infant mortality must be huge. Think of all the bugs and vermin there, as well as all the smoke.”

“No,” says Aka. “You see these children? They’re all strong and healthy.”

They seem it. They’re the snottiest children I’ve seen in Indonesia, most likely due to the kippering process, though not necessarily snottier than a primary school class in an English winter.

But the ones who make it through to the running around stage are sturdy, happy, sunny children.

They stopped head-hunting in Nome in 1942, so the story goes. “With independence,” Kores explains.

From a European perspective, the date comes as a shock. I count Indonesian independence from 1945, when the Second World War ended, the Japanese left and the new government declared its independence (though the Dutch did not give up until 1949).

These guys count it from when the Japanese kicked out the Dutch in 1942. (That’s five years too late for living memory in a community with life expectancy like this.)

“What happened?” I ask.

“Not allowed,” he says.

“Police?” I ask.

Inquiries get me no further.

I’m figuring – and this is raw conjecture – that the Indonesian forces of independence had a quiet word with the king, that taking of heads played no part in a modern nation state…

Head-hunting seems, quite frankly, not to have bothered the Dutch. In the Spice Islands, we learnt that a man could commit mass murder to avenge the death of a dog. In fact, a myriad peoples across East Indonesia knew no law beyond their own tribal adat until, often, many decades after independence.

I’m not sure what this says about me and Z. But it’s not the head-hunting that gets to either of us. It seems, well, comprehensible as a warrior way of living.

It’s the smoke.

Now, in East Indonesia we have slept on board platforms under palm leaf shelters, on rice sacks on dried up river beds, peed in the bush and wiped on leaves, watched buffalo sacrifice and men beating hell out of each other with deer antlers, and met nomadic hunter-gatherers, who hold their magic in rattan belts.

We can see the appeal of these ways of life. It’s different, sure. But comprehensible.

But this kippering in the dark? It’s inexplicable.

There are so few peoples in the world who have chosen to live without a chimney, or, rather, some means of drawing smoke out of their habitation.

Here, we are welcomed into a beehive hut, to sit in semi-darkness around a kerosene wick: cooking fire and a cooking pot improvised from an old biscuit tin in one corner, a tiny platform where the family sleep in another.

The families of Nome can, and do, raise eight or more children in these smoky pits, though some now are beginning to add a second hut, on a rectangular frame, with an open cooking place, to their traditional way of life.

Out in the bright sunlight, eyes adjusting, we sit with the women of the village for a while, passing around the betel we have brought.

Chewed with a little lime powder, and the peppers they like to cut it with out here, it produces a race of the pulse, an increase in the pace of thoughts, a dryness of the mouth, like a dab on the gums of heavily cut speed.

I pass on the betel, and hand out cigarettes. A woman of quite dazzling bone structure, with the face of a 1930s model, a second-hand jacket flowing loose over her ikat sarong, inhales deeply and squints into the sun.

It’s hilarious. Everyone – women and children – fall about laughing.

“What’s so funny?” asks Z.

“I don’t know,” I say. “I think it’s that she’s smoking, and she’s not allowed to do it.”

And as we bike back to the never-ending sprawl of Kefamenanu, the biggest small town in Indonesia, almost 4000k on our motorbike, and on the very last island before we embark for Papua, our minds are running, not on the heads at all.

What strikes us is the smoke. The dark. A humour too simple for us to understand.

A very nice and interesting article!

Thanks, Melvin!

wow. i interviewed Paul Raffaele, about his book, Among the Cannibals: Adventures on the Trail of Man’s Darkest Ritual. it was an incredible read. sounds like your experiences will stick with you for a while!

I haven’t read that. The most fascinating one I’ve heard of is in Southern Papua, where the tribes would attack a village, butcher and eat the parents, then adopt the children — telling them where they’d come from, and that their birth parents had given their bodies to make food for them (older children would eat their parents’ flesh as part of it). An ex-boyfriend witnessed cannibalism by Druze fighters in Lebanon, so there’s a complex history of it. I’ll need to look it up.

I always love your posts because you have such a great way of telling a story. This post was no exception and very interesting to read.

Thanks, Matt… We were hoping to meet people who lived through it — but headhunters don’t live that long.

Interesting article; I am sure that most of us had no idea how these people live and it is quite fascinating to follow along with your story and get some perspective on their lives.

Thanks, Scott. I was a bit disappointed we’d missed the last living memory by five years — I was really hoping someone would still be around. But of course the life expectancy is pretty low there.

Thanks for this article, Theodore. I am from Kefamenanu; my parents and my family dont even mention about headhunting. We dont do that again. I think, nowadays, so many Timorese from my generation didnt know about headhunting — as I didnt. I ask your permission to translate this article into Bahasa Indonesia and post it on my blog.

Hi Felix, Of course you are welcome to translate this old article and put it on your blog: I hope it’s reasonably accurate! Please do link back to the original once you’re done, so that people can click through if they want to… Cheers, Theodora!

Hallo Theodora, I am not a prof translator, but I try my best. If you have enough time to see it, click the link bellow and feel free to give a word if you think its not accurate anough 😉

https://sufmuti.wordpress.com/2017/02/03/ayahku-pemburu-kepala-manusia/

Thank you, Felix! My Indonesian is terrible, so I’ll take your word for it…