Scenes from a Forgotten Conflict

An adult woman weeps as she recalls a childhood spent in prison. The time the soldiers forced her to torture her mother. And the times the soldiers tortured her to hurt her mother more.

A man who was ten years old when his big sister was taken recalls how she never recovered from her rape.

A woman’s body, hooded, almost naked, lies bloodied on the floor, a soldier’s boot pressing down on one arm, and the pristine white trainers of a militia man incongruous to one side…

And a party of schoolchildren sit, pens and notebooks in hand, in the Garden of Contemplation at the Timorese truth and reconciliation commission, a series of low barracks that were once the Balide prison in Dili, East Timor.

East Timor… Timor Leste… Timor Lorosae…

Call it what you will. Few people outside Australasia have even heard of this little nation, surrounded by Indonesia on three sides, Australia a few hundred kilometres to the south.

Fairly few of those remember the conflict that rocked it.

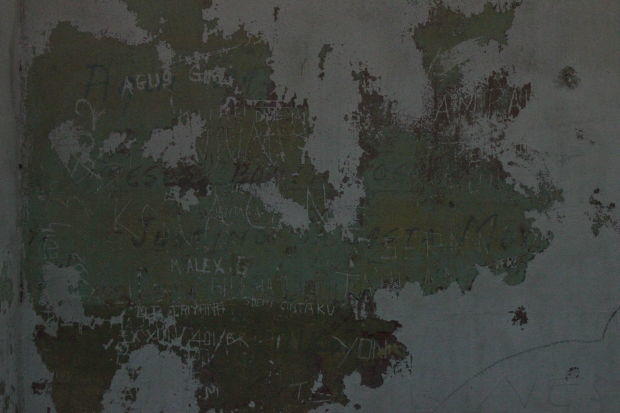

Let alone the prisoners who drank water mixed with chicken shit and soap, were tortured, sexually assaulted and sometimes murdered, within these tiny cells. Of some, only their graffiti remains.

Not many remember the massacres the Indonesian army committed over their 25 year occupation -– and local militias, too, Timorese against Timorese.

The forced march, where the army walked perhaps as many as 60,000 Timorese across the island in a human chain to force resistance fighters out of hiding. The hundreds of protesters shot down in the cemetery of Santa Cruz.

And the men, women and children who died in the famine that followed the maelstrom of forced relocations, emptied villages, abandoned farms and livestock…

It’s worth remembering, sometimes. It’s worth understanding how many Western powers, panicked by a dictator’s stories of communist infiltrators, not only stood by but armed the invaders.

And so, if you come to Dili, you should visit the Balide prison. Less stark in its horror than Tuol Sleng, the Khmer Rouge prison in Phnom Penh, it will open your eyes to the bloody history that shadows the future of East Timor.

The Chega! exhibition is at the CAVR (Commission for Reception, Truth & Reconciliation), Balide prison, Estrada de Balide, Dili, East Timor. Many locals and taxi drivers don’t know it, so look for the UNMIT compound next door. To learn more about truth and reconciliation in Timor Leste, visit CAVR’s website.

Your right. I am pretty well informed and I don’t know anything about East Timor.

You just can’t make this stuff up. Unbelievable.

My first thought when reading this is how my daughter is convinced there are no bad people in the world, or at least not where we live. Curious how your son responded?

Thanks for letting us in on such an obscure, but important part of the world. I have a feeling that sometime in the future I will be coming back to your post to help my kids try and understand that the world is good, but you really have to keep an eye on it.

Well… He’d seen Tuol Sleng in Cambodia, which doesn’t exactly inure you to horror, but much worse things were done there than in Balide: only four people left there alive, and torture was its mainstay (including systematic murder and torture of child prisoners, some of whose photos are on display there). After the Cambodian genocide, and talking to people who’d been through it, you have a blacker view of what humans are capable of — so we talked about the prisoner experiment at Stanford, in the context of that question, that most humans can be turned to bad things by authority. So: he was shocked by Balide. But not as horrified as he was by Tuol Sleng. It does not, however, shatter his expectations of how humans will be to him, or his general sense of kindness, expectations of kindess — he understands it, as with the Rape of Nanking, as one example of the sort of thing totalitarian regimes can force people to do. He frames these experiences in terms of brainwashing, which, I think, the best way to see it — particularly as regards the child soldiers of the Khmer Rouge, but also as regards the adults who fought in the militias and served in the Indonesian Army here.

It is not just here in the west that we didn’t know what was going on – I was in Bali in the 80’s and never, ever read anything or heard anything of what was going on there. Just that there was “instability” in the area. There was, however, the general feeling that Bali was a little oasis of safety from the corruption and cruelty of the general Indonesian military and police force. Just shocking to hear & see this.

I think no one really knew much of what was going on until the Santa Cruz massacre came to Western attention. Communications were not good, and Timor is a long way from Bali, plus the media was controlled. Like what’s happening in Papua now (and Acheh, too), I think it’s presented as insurgents, or instability, rather than repression. I think Bali, also, has always been sheltered from the larger excesses of the military — and sympathetic to the control that comes out of Java. So I’m not surprised you heard nothing of it. It would have been more surprising, in a way, if you had heard anything…

how awful. and how important, for us to learn and know this.

I had shivers going down my spine reading about this. It’s one thing to hear that Aussie troops have been sent there for peacekeeping corps, another to read about it as such terrible abuse.

I was shocked, too. I knew very little about Timor Leste before we got there, but the facts that it had been Portuguese, been occupied, become independent. I didn’t realise that there were human rights abuses on this scale — the dictatorships as a whole committed human rights abuses against their own people, also, but I had no idea that the horrors were this vast… There are still a lot of Aussies in East Timor — a big AusAid presence, among other things — but I can see how, so close to Australia, it must be shocking as an Australian.

Random and senseless brutalities such as these made me boil with anger. I was growing up in Indonesia around this time and heard very little of this. God knows what other atrocities are being committed around the world right now, hidden and unknown to the rest of us.

That’s a brilliant insight. I think it is only when a nation gains its independence — or, as in South Africa, where a regime is removed — that we see the other side of what can be presented as insurgents/terrorists… I had a funny feeling crossing the border, actually, with the chief of police befriending Z, asking him about Timor Leste, making faces, and wondered whether he’d served there when it was Indonesia.

are you two ok?

Yes! We’re fine. Just had no internet for a while…

I went to Timor Leste sep 2010 for a study tour with nine other students and we went to this prison and the lady that was our guide was a prisoner of that jail and what an eye opener. ic uould only imagine when she first started as a worker of this place of how hard it was at first to speak of what happebned to her and her mother but of the strenght that she has now of doing it for so long and the power she has to expose the bastards for what they did to these people. i could not do it.

Thanks for your comment, Ivy. It’s a very disturbing place, isn’t it? And, yes, I’m awestruck by the amount that people can survive and still live to forgive and talk about — which is, in a way, one of the most inspiring elements of that prison.