Petrified in Petra (1)

Back in the UK, for our first visit after over two years travelling, at a goodbye dinner that was, sadly, kind of a “hello dinner” too, the conversation turned to Petra, and the iPhone pictures came out.

“You enter through the siq,” says one friend, brandishing an iPhone pic. “And that’s obviously amazing, but when we were up at a different part of the site there were people who looked as though they’d walked in from the desert, and that looked really well worth doing.”

This, as these things do, sat in the back of my brain until we actually got to the site, and then began to surface.

Now, the siq is, indeed, amazing. If it seems familiar, it’s because it’s the narrow canyon Indy rides down to discover the Holy Grail in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Still, being me, I wanted to find the other route. Y’know. The one through the desert.

Petra is, as I’ve mentioned, enormous.

But all the same, day one is easy enough.

Nobody tries anything clever on day one.

Those folk who fall off the cliffs to their deaths, get washed away by flash floods or get lost in the mountains for two days until Bedouin search parties track them down?

They’re all on day two, or even day three…

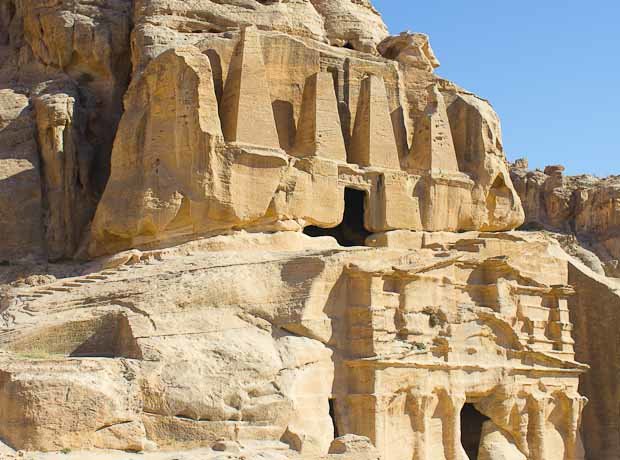

We wander down to the site along an easy path lined with persistent-for-most-of-the-world-but-nothing-after-Egypt donkey boys and horse and carriage salesmen, gawping at the rock tombs and those weird sandstone formations like waxy Chianti bottles in an Italian bistro that we loved in the Sinai.

“Look, Z!” I say, in full tutorial mode (I have bought a book on Petra at eyewatering expense and intend to make good use of it in the furtherance of my son’s global, if patchy, education). “These are djinn blocks, or representations of the gods as cubes. Can you think of any other religion that has a sacred cube?”

“Umm, Mum,” he whispers. “I don’t think you should say that so loudly. We are in a Muslim country, after all.”

He has a point.

I STFU.

Still, one of relatively few things known about the Nabateans who built Petra is that they exported many of their gods across Arabia to Mohammed’s people, the Quraysh.

It is Nabatean goddesses who figured in the Satanic Verses, verses which may or may not have been added to the Quran by error and then removed, and it was these goddesses who sparked the conflict between the Prophet and his parent tribe, and these weird, enormous cubes may represent them.

Or they may not, of course. The Bedouin who inhabited this site long after the Nabateans, until the government moved them on in the late 1980s, believed these blocks were home to spirits, or djinn.

Although as they also believed that Pharaoh, a demon king, had hidden his gold in an urn on the top of the Treasury, they are not necessarily to be trusted in this regard.

“Hey!” says a man with a horse, for the n-th time. “Free ride! Included in your ticket!”

“No thank you,” I say, in a refrain that is becoming painfully familiar. I know full well that neither donkey nor horse nor camel nor carriage is included in my ticket, BUT I don’t know how to say any of this in Jordanian Arabic, which has “j”s where Egyptian has “g”s and “g”s, often, where Egyptian has glottals or vowels, not to mention lots of completely new vocab. “We do not want a horse. Or a donkey.”

“Included in your ticket!” he says.

“No thank you,” I say. He trots off to pester someone else.

“Hey! Mum!” says Z. “I think I’ve worked out what his scam is!”

“Really?” I say. “I KNOW it’s not included in the ticket, but what do you mean scam?”

“It’s because of me!” says Z. “He can tell that I’m under 12 so I don’t need a ticket. So, I ride the donkey, and then he asks me for my ticket, and then I don’t have one, so you have to pay some huge amount of money.”

“That sounds about right,” I say, impressed.

Jordan is Middle East/North Africa light. I have experienced less sexual harassment here than I’ve felt in this neck of the woods EVER, outside of Israel and, bizarrely, Mauritania.

But… Jordan is still the Middle East.

“I’d never have thought of that,” I say. “Hey! Look at that tomb. What do you make of that tomb?”

“Top half Egyptian. Bottom half Hellenistic,” says Z. “Kind of crude.”

“Shall we go up and take a look in it?” I say.

We scramble up.

“Oh,” says Z. “What happened here?”

The interior looks like it’s been artexed in black tar. “Bedouin have been living here for centuries,” I say.

“Oh, so that’s their fires, is it?” he says. “Bloody Bedouin. Don’t they know it’s a tomb?”

“Nope,” I say. “It’s a house. Or a cave.”

“That’s disgusting,” he says. “It’s a 2000-year-old tomb.”

“This is a part of the world with a truly ancient culture,” I say. “It’s like China. Middle Eastern peoples don’t need to care about old stuff because they’ve got loads of it and were civilised when we were dressed in woad.”

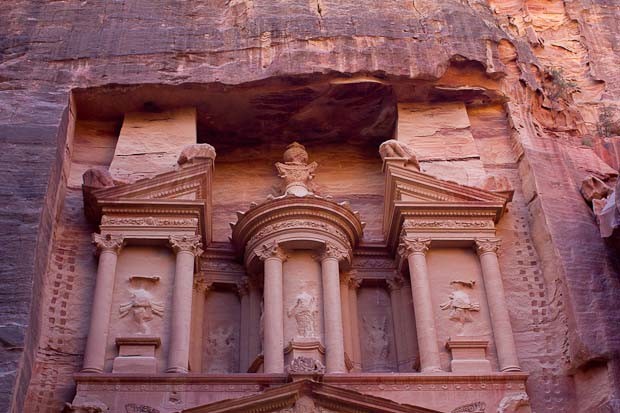

We are duly impressed by the Treasury. Well, I am.

“What do you think, Z?” I say. “Isn’t it amazing?”

“It’s very Hellenistic,” he says.

“Well,” I say pompously, brandishing my book again. “Yes and no! It IS Hellenistic. But the pointy bits on the tops of the columns are unique to the Nabateans, as are those circle decorations. And…” I consult the book again… “Those weird stepped triangle patterns we’ve been seeing on other stuff? They’re Syrian.”

“Who vandalised the statues?” he says. “Christians or Muslims?”

I consult my book. “Muslims,” I say. “But it was the Bedouin who shot up the urn. They believed it held pharaoh’s treasure so they took potshots at it to try and bring it down.”

“WHAT?” Z says. “That’s disgusting!”

“Shhh!” I say. “Half the people here are Bedouin.”

We amble down past yet more tombs (not into them, since, after Sakkara and Luxor, we have rather high expectations of tombs and, what with centuries of occupation, these have nothing in them) and hit the theatre, a splendid — if, as Z observes, “Very Roman!” – semicircle carved out of the living rocks.

At which point, Z meets two fat puppies.

And a 13-year-old donkey boy, to whom the fat puppies belong.

And the two boys, and the two puppies, proceed to race around the sand, in and out of tombs, up and down rocks, having a whale of a time.

It’s genuinely lovely.

Z made a mate in Dahab, which was easy, but one of many things I’ve been finding difficult about the Middle East in general is finding him company of his own age.

So there we stay until nightfall.

Jordan is so chilled for the Middle East that I feel able to sit on a rock and read my Petra book, the first time I’ve been able to sit and read something at a tourist site since Alexandria.

I have to fend off two hardass Bedouin salesgals who want makeup (I have none), or to swap my sunglasses for their necklaces (no way, Jose), and a few men with offers of transport of various kinds, but it’s pretty chill.

And watching Z, the donkey boy and the two fat puppies scampering in and out of two thousand year old tombs is positively heartwarming.

“He did try to sell me a donkey,” says Z, later. “But his heart wasn’t in it. He just wanted to play.”

“Yeah,” I say. “He tried to sell me a donkey too. But I don’t think that was what it was about, really, do you? He’s just a kid, playing.”

We wrap up with a drink in a 2000-year-old tomb, now converted, to Z’s horror, into a bar.

Which would, if the guys could make a Negroni, be an absolutely excellent end to the day.

The next day, I rise convinced that the alternative route my friend was talking about must be up Wadi Muthlim, a dry river bed from the entrance, which is also, according to my out-of-date guidebook, acquired at considerable expense in Aqaba, an easy scramble.

We amble down, fending off donkey guys, and into the river bed.

The tourist police beckon me up.

BUGGER! I think.

“You can’t go down there without a guide,” says the tourist policeman. “It’s dangerous.”

“It’s OK!” I say, as predatory guide-type guys begin to circle me like sharks. “Look! I have a map! I have 5 litres of water! We have food! It’s early in the day! It will be fine!”

“You can’t go without a guide,” says the policeman.

Z strops off to slump in a corner, leaving me to negotiate with the guides. They want 30 Jordanian Dinar, which is roughly 50 of your US dollars, or 30 of my British pounds, to escort us for an hour down a river canyon that we can, apparently, follow ourselves. (Did I mention the entry price for Petra is fifty Jordanian dinar? Or fifty British quid?)

“It’s dangerous,” says the guide.

“It’s not dangerous,” I say, pointing at the blue sky. “No rain! If there were flash floods, you wouldn’t be going down there. No rain today! No rain yesterday!”

“There is water in the river,” says the guide.

“REALLY?” I say, looking emphatically down a firmly dry tunnel.

“You can go down the other way,” says the tourist policeman, helpfully. “Coming BACK, you can walk down Wadi Muthlim, because we can’t see you. But if we see you, we can’t let you pass.”

The guide, to his credit, agrees with this.

We haggle a bit more, and he reduces his price to 25 dinar.

“Look!” I say. “In Jordan, a man can earn 200 dinar in one month. You want 25 dinar for ONE HOUR?”

“Yes,” he says. “The tourists, they pay 10 dinar for a short ride on a horse. Five minutes on a horse, they pay 10 dinar.”

It’s a fair point. “Mum,” says Z. “Let’s just go down the siq.”

The centre of Petra, with its main street flanked by river beds, and the rubble of some seriously substantial masonry buildings, destroyed in one or another earthquake and/or cannibalised by Crusaders for their clifftop castle, requires some imagination to bring it to life.

Mercifully, Z has this, in spades.

“Wow!” he says, looking at the remnants of the colonnades, and some masonry that was once a fountain, and a temple so gigantic that, if you hadn’t been to Egypt, it would leave you absolutely floored. “This must have been beautiful!”

“Yeah,” I say. “Imagine. With the spice trains and the slave caravans coming in. That would have been the fountain there. And that was the swimming pool, over there… There’d have been houses, gardens, little shops…”

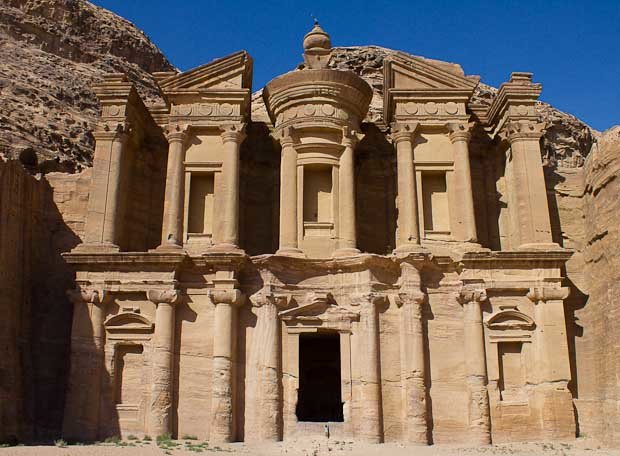

We eat lunch at a buffet, explore the museum, and head up a long, dramatic ascent to the monastery, past tombs that have been transformed into garages.

One of the lovely things about Petra is the way that erosion has revealed the patterns of the sandstone, great whorls of the stuff, like a child’s ball of plasticine at that lovely marbled stage before it turns putty coloured.

Back in the day, as a little bit of paintwork on the back of the temple makes clear, it would all have been whitewashed and party-coloured, and most likely equipped with trompe-l’oeil doors.

We stop for a coffee en route and have a chat to the guy in the store about the path to Wadi Muthlim, which is, he says, quite easy to find from behind the big tombs.

“You know you can walk all the way to Little Petra from the Monastery?” he says.

I did know this, in fact. And it dawns on me that this must be the route in from the desert we’ve been looking for.

And, damn! We’ve missed it.

Because with 800-odd steps to the top, I am buggered if we’re walking this again.

Up at the top, we gawp at the Monastery, and clamber in and out of it, and I wonder why it’s the front of my calves, not the back, that are aching.

“Look!” says Z. “There’s someone up at the top! How do you reckon I get up there?”

“You can go up,” I say. “I’m not. And you need to stay well back from the edge.”

He hums, haws, and doesn’t go up.

Z tries and fails to negotiate a Twix down from 2JD ($3). No joy.

I realise it’s getting quite late in the day.

And, because Petra is so bloody enormous, that means we need to start thinking about how to exit the site.

I’m wondering whether we should negotiate Wadi Muthlim. Although if the chap is telling the truth about there being water in the river, then we might have to turn back, and Z will curse my bones if I get us lost towards nightfall.

No, I think. Let’s head down.

We head down, and bump into the chap who’s sold us coffee earlier and given us directions to Wadi Muthlim.

“If I were you,” he says. “I’d walk out from the Treasury towards Little Petra. It’s really lovely at this time of day. The rocks are pink…”

We hum, haw and haggle. He can find us a guide for 20JD, a fee I don’t mind paying because it’s a walk I know we can’t do on our own. And, as is not unusual for Bedouin, our guide is in fact his cousin.

Shadi was, like a lot of Bedouin around here, born in one of the tombs of Petra.

The caves and tombs were home to countless generations of Bedouin until the 1980s, when the government moved them out into villages. (On the plus side, unlike in the Sinai, the Jordanian government put measures in place to ensure they profit from the tourism on their land.)

Like many younger Bedouin round here, Shadi wears kohl, traditionally worn by men only at weddings and parties, both as style statement and a substitute for sunglasses (which is how the Ancient Egyptians used kohl too).

“We’ll stop at a village of the little people,” he says.

“The little people?” I say.

“The Edomites,” he says. The Edomites figure in the Old Testament as bitter foes of the Israelites, and occupied this part of the world before the Nabateans (who seem to have got on well with the Israelites) pushed them out.

“Cool!” I say.

It’s a beautiful walk through the col and along the cliffs, and I’m beginning to think that, after Tiger Leaping Gorge, I really do have this vertigo thing well – not exactly conquered – but perhaps a little more under control.

Then the path narrows, to about 18 inches or so. I inch along it with my hands on the wall, trying not to scream at Z to be careful.

And then the path disappears altogether.

We have to climb up and over a bulge in the rock, over a near-vertical drop of several hundred metres. Without ropes.

Which is when I realise that my vertigo is in no shape and form under control. Not least because I haven’t spent the day preparing to test it.

My pulse rate goes through the roof. I have to endure two waves of crippling fear. The first for my son’s safety. The second for my own.

Shadi crosses first.

Then Z goes after him, climbing up and over the path that Shadi’s taken, with Shadi standing guard.

I cannot, actually, look as he negotiates it – I am staring fixedly at the rock in an effort not to look at what’s below me – but I do scream, involuntarily, and unhelpfully, “BE CAREFUL!”

Z is safely over. I take my cheap Egyptian flip flops off. “Leave your shoes,” says Shadi. “I’ll come and get them.”

I start to scramble up. “Don’t look down,” says Shadi. “Just look at where you’re putting your hands and feet.”

I watch my hands on the rock. It’s like they belong to someone else. It feels like my heart is trying to jump out of my chest.

Keep going, I say to myself. Whatever you do, don’t freeze. And don’t look down.

And then I’m up, onto the ledge, under an overhang and on top of the slope that leads down into the void.

“Right,” I say, in a tone I think is calm but clearly isn’t. “I think I’m going to crawl for this bit.”

I crawl. I turn, agonisingly slowly – it’s quite hard to turn round without looking down.

And I descend, onto a path that widens rapidly to a princely metre or so. “Wow!” says Shadi. “You broke the red line of fear.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I’m not that good with heights.”

“Sometimes, when I guide trekking groups,” he says. “We have to carry people over this.”

This makes me feel a little bit better, if not much better. The adrenaline takes a long time to fade.

There’s not much to look at in the Edomite village, except we can see why they’re called “the little people”, because their houses, albeit stone-built, were tiny, but it’s kinda cool to see it anyway, given it dates back to Old Testament times.

“You know, a team from a university spent three months up here,” says Shadi, clearly rather mystified as to why anyone would care about the “little people”, when guys from his tribe routinely – so they say — find Nabatean and Roman gold in the mountains.

And then, miraculously, amazingly, a mother bird and a baby bird come rushing out of a shrub.

Shadi catches the baby and hands it to Z. It’s a lovely moment.

A flight of stairs appears, not carved by the Nabateans, but built by the Bedouin, and we head out into the flat, having seen, I realise, not a single soul since we left the Treasury.

The sky is starting to shade towards sunset, and a wide plain opens up, studded with boulders. Outside one large boulder, there are camels grazing, a flock of goats, and a pickup truck.

“That’s my cousin’s house,” says Shadi.

“Oh! So they still live in caves out here?”

“At Little Petra, yes. It’s just Big Petra we’re not allowed in the caves, though we still come out and sleep here when we can.”

Shadi, like most Bedouin here, has quite unfeasible numbers of cousins and uncles, and a discreet aversion to the folk who live up in the town of Wadi Musa, who are fellahin, or farmers, or even (heaven forfend!) Palestinians, rather than Bedouin.

Another pickup is parked on a rock with a view over a gorge. “They’re my cousins too.”

We wander over, and the sun begins to set, with camels silhouetted against the horizon, just like in the sand art they sell outside Petra.

Jordan, I think, as we sit on the rocks with the Bedouin, chatting dilatorily to Shadi and his cousins, and watching the sun set, is the Middle East light. But it’s still the Middle East.

Very impressed with Z’s knowledge of ancient architecture!

Yes, it has sunk in, LOL…

What a day! I can taste your fear because I’ve been there myself – and I do think it’s just about impossible to watch your kids do something like this without screaming.

I am very impressed with your son’s knowledge and wonder where all these travels will lead him in his adult life.

That is, of course, the big question. He currently wants to put a colony on Mars. Or build computer games. The family all thought he’d be a politician because of his, umm, verbal style from a young age.

But I will be very curious to see. God. He’ll probably end up as a banker…

OMG!!! you broke the red line of fear. that’s a huge accomplishment. i think i’ll just live vicariously…

I really did not enjoy that stretch at all. As I am sure you can imagine, Jessie.

Fun read! I went to Petra when I was in college (about 14 years ago) and got left behind by my group. I remember walking out alone being so scared that I would end up in one of those caves. Then coming to a group of what seemed like a hundred muslim men (but probably more like 30) on horseback holding guns. My 20 year old sheltered Mid-West American self was terrified walking through the group. I think I may have crossed my redline of fear that day. The mind is funny thing.

It is, isn’t it? I wonder what they were doing. Bedouin going hunting? Bedouin squabbling? Or something more sinister to do with the borders in the region?

Your son is very knowledgeable! And I don’t like heights either.

Thanks, Mary. Because we unschool, he tends to learn a lot of relatively obscure stuff about where we are — but the Middle East is amazing for history. Incredible, in fact.

Wow, I didn’t know Petra was so expensive. Looks lovely, and I feel like your son’s getting the best education of all.

I think he is too, so thank you! And, yes, it’s expensive BUT if you do the three-day ticket it works out quite affordable, and it does merit spending three days there. Also, as Gillian pointed out, it’s possible to do the walk up the wadi without a guide (just bear left at the point where it splits, into the narrow part), provided you are not the killer woman + child = vulnerable combo.

I would like to let you know that Muslim don’t actually consider the cube in mecca sacred. They don’t even worship the cube. Muslim pray to One God and they all praying in one direction to symbolize that, with or without the cube.

Thanks, Gul. I’m aware that, of course, Muslims don’t worship the cube per se, as earlier people did, but the One God, but I guess I used the term sacred because it has a part in the religious ritual of the hajj: maybe I should have said “ritual” rather than “sacred”?

Girls be aware that in Petra a scamm business is going on.

Please check this out:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Stop-the-Petra-bedouin-women-scammers

http://www.beznessalert.com/beznessblog/?p=933

Guys will try everything for you to fell in love with them to stole you money, have sex and cheat on you.

Right, so, do Jordan before Egypt?

There’s more to Egypt than there is to Jordan, but Jordan’s definitely an easier introduction to the magic of the Middle East than Egypt, which routinely makes me stabby. I love the place, and all, but some of the sexual harassment can become very, very wearing, whereas in Jordan it’s usually just sales stuff…

I’ve spent a good bit of time in India, so feeling both stabby and enamoured with a place is something I’m familiar with. The Middle East is somewhere that I feel a real time cruch to get to for fear it will become ever harder to access and/or be destroyed if I wait too long.

Yep. I still regret not making it to Syria while that was a possibility. And hope one day to be able to visit Iraq…

My sister and I were plotting a trip to Syria with a friend from there when it all fell apart.

I can’t imagine how rough it was for him, to go from describing the wonders we could visit together to wondering when/if he could return himself.