S-21: Genocide for Beginners

“Kneel down, mum,” Z says. “Close your eyes.”

He fumbles with my hair. We are in the courtyard of Tuol Sleng prison, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, AKA S-21, where teenage true believers tortured and killed over 16,000 people, from babies to geriatrics.

On a concrete bench under a papaya tree a crimson-clad monk sits contemplating, Nokia in hand. The place is very still.

I open my eyes. Z has gathered a frangipani flower from the grass and put it in my hair. I thank him.

The four solid, balconied buildings which line the courtyard still have the unmistakable outline of a 1960s secondary school, which they were before the Khmer Rouge closed the schools and turned this one into torture chambers.

In the courtyard is the original gym equipment, used for a form of torture from which guards revived prisoners by dunking them headfirst into barrels of “liquid used for fertiliser”.

We go to the first classroom. It contains very little: a metal, slatted bed, rusted iron shackles attached to it by a solid metal bar, a rotted ammunition box the inmates used for bodily fluids, and a stark, black and white photo of an emaciated, unnamed victim, throat cut, slumped across this bed.

In the neighbouring classroom, the body in the picture is on the floor, and from its dark, unnatural plumpness had been rotting in this clammy heat for some time.

In the third room along, a petrol can and plastic plate lie on the bed. We leave the flower as an offering.

One of the most perplexing things about Tuol Sleng is that, often, neither interrogators nor prisoners knew why they were there. Despite the bizarre obsession with documenting all that happened here, prisoners arrived without paperwork.

And the functionaries who arrived at their homes in the middle of the night generally did not bother to explain what crime or association had been committed.

Records of interrogations, which are legion and detailed, and the testimonies of the seven known survivors, show that the usual opening gambit was to ask prisoners why they were there.

When they, as often, genuinely did not know, they were tortured for days, weeks or even months until they confessed to something, anything, and named any names they could recall. After they were killed, their families generally followed.

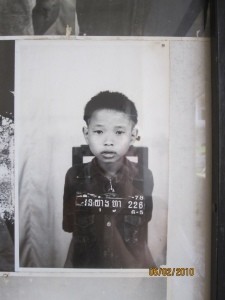

The next rooms are filled with ranks of mugshots, expressions varying from fear to sorrow to confusion to acceptance, defiance and, perhaps most poignantly, amused disbelief.

One of the upper floors is split into the original wooden cells, 80cm wide by 2 metres long, in which prisoners were shackled.

Z goes very quiet and decides he’d rather not see more. “It seems wrong to be looking at all these people as a tourist,” he says. “I think you should only come to somewhere like this to grieve for the people who died.”

But seeing the paintings by one of the survivors depicting life inside Tuol Sleng, there’s a case for remembrance. And he doesn’t think we were wrong to go. Still, we won’t be visiting the killing fields at Choeung Ek.

The picture really brings it home. I remember an article years ago about Tuol Sleng which was illustrated, among other things, with the rules for behaviour while being tortured – it’s never left me.

I did enjoy the bus journey from hell, though – as long as I never have to do one like it myself!

Love to you both, and hope to skype soon.